Visual impairment in the classroom

Visual cues are central to most early childhood education systems. Consider the number of school lessons that revolve around students writing on the blackboard or reading off of photocopied handouts! Every subject, from math/maths to spelling and even geography, requires reading and writing.

That’s why whether visual impairments are moderate, severe or profound, they often interrupt a low vision student’s ability to participate in regular classroom activities.

In the past, students with visual impairments were placed in special institutions or programs; however, today most are educated in a classroom with other children who are not visually impaired.

There are a number of reasons for this, including practical considerations, such as getting a child used to the independent education systems he or she will face in future high-school, college and university endeavors, as well as more social ones. Attending regular classes helps students with visual impairments feel “just like everyone else.”

That’s why it’s so important for parents, educators and specialists to understand how low vision students can be successful in the classroom. There are plenty of resources and materials that provide the assistance these students need to join in reading and writing activities.

Given the right training and tools, children with visual impairments will develop the same early literacy abilities as their peers and master the coping skills they need to work around their impairments.

What is low vision?

Children and adults with low vision are not considered legally blind, they simply have reduced vision at or lower than 20/70. Students who are blind have vision that is at or lower than 20/200. Nonetheless, only 15% of students with visual impairments are considered to be completely blind, with no light or form perception ability.

That means even legally blind children may have some useful vision.

Early education for the visually impaired

While civilizations as far back as the Ancient Egyptians have been interested in education for the blind, it was not until the 18th and 19th centuries that specialized schools were first created. This was thanks in part to the development of Braille, an embossed reading system which allowed blind or visually impaired students to read using their fingers.

Surprisingly, the idea for Braille was first introduced in a military context as a night reading system soldiers could use to silently pass messages in the dark. The code, made up of dots and dashes and written on thick paper, was refined by Louis Braille to include just dots, with each letter able to be read by one stroke of the finger. It was published in 1829 and then again in 1837.

As the Braille system became widespread, access to education for individuals with visual impairments increased. The early focus of British, Scottish and French programs had always been on teaching handicrafts, but in 1835 the Yorkshire School for the Blind in England became the first institution to teach math/maths, reading and writing skills.

In the early 1900s, blind students began joining their local schools, with assistance from trained special education teachers, and today, most visually impaired students attend regular school systems where they learn in classrooms with students who do not have visual impairments.

Low vision in the classroom

In a school environment, visual impairments can cause difficulties when it comes to traditional reading and writing activities, reading at a distance, distinguishing colors, recognizing shapes and participating in physical education games which require acute vision, such as softball and kickball.

Children with visual impairments often start off learning to read and write with the assistance of low-tech solutions, such as high-intensity lamps and book-stands. Sometimes screen magnification and computer typing and reading programs are used. In other cases, low vision students will learn to read using the Braille system over text, or a combination of the two.

However, as students progress through early grade levels and reading and writing activities become more demanding, periodic literacy skills assessment is required to ensure additional resources and adaptive strategy instruction are provided to meet their needs.

In the best-case scenarios, children are taught by special education instructors and regular teachers. The result is a comprehensive and personalized approach to education that addresses the individual needs of children with visual impairments and which helps them achieve their academic goals.

The importance of computer skills

Magnifiers and enlarged print resources can help students during the school-day, but IT training does wonders when it comes to encouraging literacy skills in and outside of the classroom.

For those students with visual impairments who do not master Braille, making use of technology to facilitate reading is fundamental. In fact, most talented Braille readers prefer to use computers or tablets when reading for fun anyway. And students who learn to use a computer not only find homework easier to complete, but often become faster readers.

It is simply more efficient for low vision students to use a computer and word-processor over reading paper books and handwriting. This is particularly relevant at a high-school level, when reading and writing assignments become lengthier and more challenging.

Touch-typing for low vision students

Having the ability to touch-type provides students with an opportunity to navigate computers with ease and keep up in a busy classroom environment. Sometimes teaching children who are as young as 6 and 7 to use a keyboard has been shown to make a difference. Learn more about teaching typing to kids.

This is because typing is a relatively low-tech approach that grants low vision students a large amount of independence in how they make use of technology.

There’s also the feel-good factor of giving children with visual impairments more confidence and self-esteem.

A touch-typing course broken down into multiple levels allows students to work through the material at their own pace. Additionally, there’s the achievement and pride in being able to touch-type ahead of their peers.

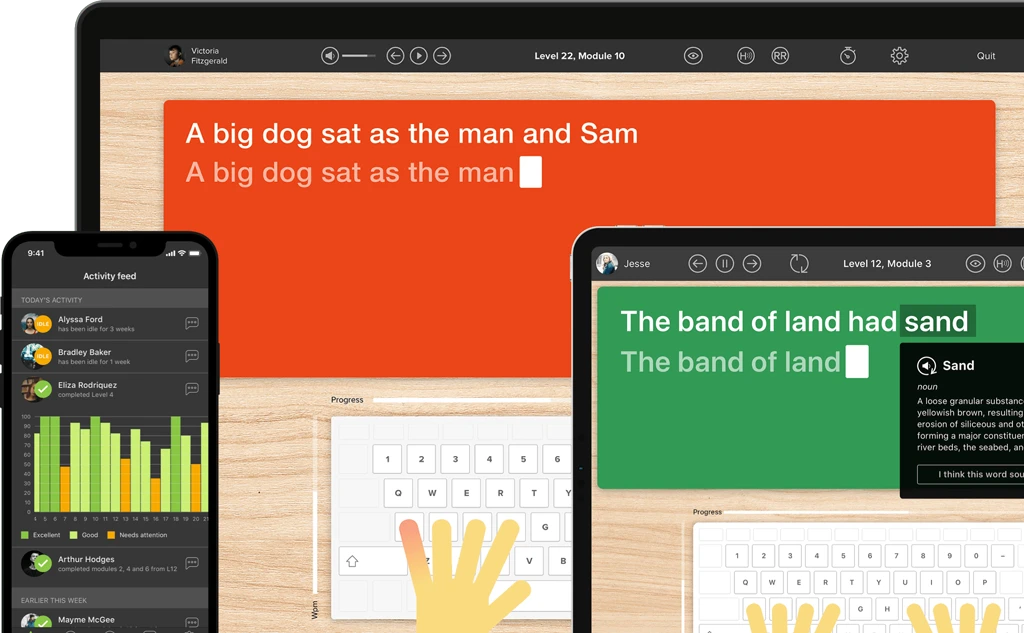

Because of its inherent flexibility, the Touch-type Read and Spell course has been successfully used in teaching students with visual impairments to touch-type. It allows for adjustments in text size and font and background color.

TTRS’s main advantage is its multi-sensory approach, which combines audio and tactile learning. This means even completely blind children have learned touch-typing with TTRS, by pairing audio instructions with physical movements, allowing information to flow freely through the fingertips and onto the computer.

Tips for teachers working with students who are visually impaired

Educators who are not specifically trained in assisting children with visual impairments often wonder how they can adjust their teaching to help students be more successful in the classroom.

Allow low vision children to choose their seat.

It can be both embarrassing and unnecessary to single out a student with low vision and force them to sit in a particular seat because you feel it provides them with the best view of the board. Allow students with low vision to take control of their learning and identify the location that is best for them.

Read what you write on the board out loud.

Teachers should vocalize the text they write on a blackboard, white-board or smart-board to help visually impaired students who may be struggling to read the text. This may be due to anything from text size, to distance from the board, angle of sight, glare from a window or clarity of print. It can also be useful to provide a paper handout of materials that are presented on the board, or an electronic copy for which the text can be enlarged, to make it easier for students to follow along without tiring.

Use paper handouts printed in high-quality.

Many elementary school activities and resources are photocopied and provided as paper handouts. It’s crucial to ensure they are printed with strong contrasting colors as opposed to faded greys, to make it easier for the visually impaired student to read them. Additionally, handouts can be emailed to the child who can use text to speech facilities to make access easier.

Learn more about typing for the blind.

For teachers

TTRS is a program designed to support educators in teaching students touch-typing, with additional emphasis on reading and spelling.

Chris Freeman

close

Can an Orton-Gillingham approach to literacy help your child?

Take a short quiz to find out!

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress