Identifying dyslexia in 3 easy steps

Dyslexia is a specific learning difference that can affect both children and adults and cause difficulties with reading, spelling and math. It’s important for parents and teachers to understand that dyslexia does not affect intellect. Rather, it is a different way of processing language in the brain.

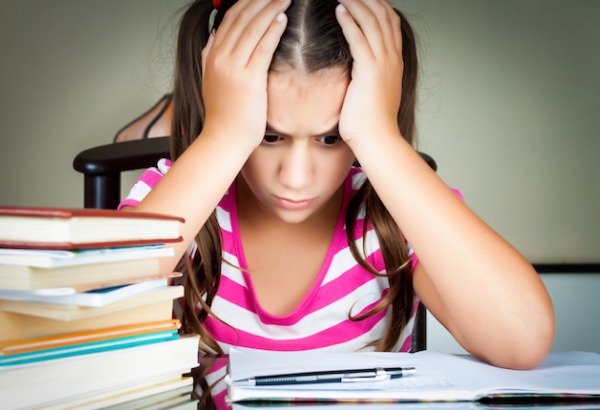

Often individuals who are dyslexic struggle to split words into their component sounds. For children who are learning how to read and write, this can cause frustration and poor performance in activities involving literacy skills. Because reading is required across the curriculum, students may quickly fall behind their same-age peers and lose confidence in the classroom.

That’s why it’s important to recognize the symptoms early on so children can gain access to appropriate coping strategies and accommodations that can help them achieve their full potential at school.

What makes dyslexia especially difficult for educators to identify is it comes in many forms and no two children will present the same set or severity of symptoms. Additionally, many of the characteristic traits are common amongst children who do not have dyslexia but are in the early stages of learning how to read. For this reason, if you suspect dyslexia is causing a student to experience difficulties in the classroom, it is best to take a multi-step approach to diagnosis.

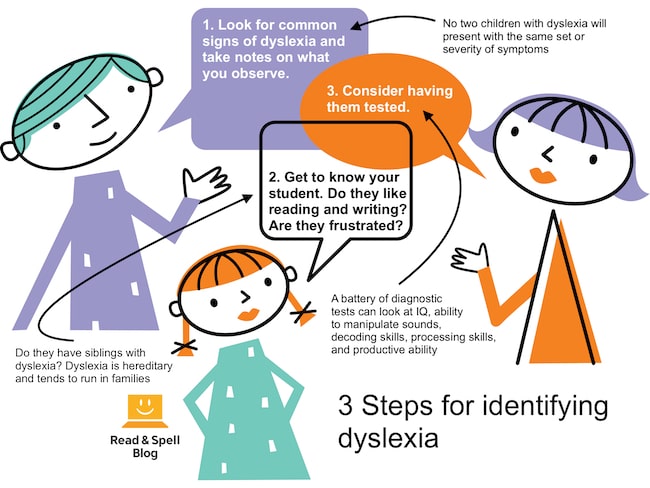

Step 1

Begin by looking for common signs and symptoms associated with dyslexia and taking notes on what you have observed. How does the child’s work and reading ability compare to that of same-age peers and does their performance fluctuate from day to day or week to week?

Step 2

Next, get to know your student. How do they feel about schoolwork? Are they frustrated? Do they like reading and writing? What’s going on at home that might be impacting their ability to focus during the school day? Do they have any brothers or sisters who have dyslexia? Dyslexia is a hereditary condition that runs in families so having a sibling or a parent who is dyslexic can make it more likely that the child is dyslexic too.

Step 3

Finally, consider providing a battery of diagnostic tests that measure a child’s IQ, ability to manipulate sounds, decoding and processing skills, and productive ability. When students are of average or above average intelligence yet unable to demonstrate this in reading and writing, some form of dyslexia may be present. The same is true for motivated students who enjoy learning via activities that involve speaking and listening but lose their confidence when faced with reading and writing based tasks.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia can show up in different ways depending on the individual, but a good way to describe it is a difference in the way the brain processes information.

There is often a phonological component which means people with dyslexia may struggle to map sounds to letters and hear the phonemes that make up words. Sometimes dyslexia can affect perceptual skills and be associated with trouble recognizing words in reading. Certain individuals with dyslexia find it difficult to process and retain images. In addition to literacy skills, dyslexia can also affect memory, planning and organizational abilities. Learn more about the different ways in which dyslexia presents.

Keep in mind it is possible for an individual to have more than one learning difficulty. People with dyslexia may struggle with math; this is referred to as dyscalculia. Dyslexia can also co-present with fine motor skills disorders and attention difficulties. A child can have dyslexia and dyspraxia or dyslexia and ADHD.

When dyslexia goes undiagnosed, children are at risk for developing low self-esteem and a negative attitude toward school and learning. They may fail to do their homework or refuse to participate in classroom activities, and acting out is common.

Signs of dyslexia in children

-

Difficulty manipulating the sounds in words. Phonological awareness is one of the key pre-literacy skills required for reading because it helps children break spoken language down into sounds that can then be paired with letters of the alphabet. If a pre-school aged child struggles with rhyming or songs like Old McDonald and Bingo, they may need extra phonics practice to help them notice and identify the sounds and sound patterns that make up words. Phonemic awareness also encompasses the ability to blend sounds to create new words. Learn more in these articles on pre-literacy skills and phonemic awareness.

-

Hesitancy to read aloud both alone and in a group setting. Sounding out words is one of the first steps in early reading. Beginner readers typically read aloud, even when on their own, sounding out every word until they reach a stage where familiar words are recognized more quickly and can be read via sight. If you suspect a child has dyslexia, it is best not to call on them to read aloud unless he or she volunteers. That’s because dyslexic students typically struggle with decoding and may experience embarrassment and high anxiety when they are expected to read in front of others. Learn more about reading and sight words.

-

Poor and inconsistent spelling. Students with dyslexia often have trouble spelling for the same reasons that cause them to struggle with decoding. Spelling requires children to identify the sounds in words so they can then translate them into letters and letter combinations. This is made even more difficult in English because of the high number of homophones (words that sound the same but are spelled differently) and a lack of 1:1 sound-letter mappings. The main thing to look for in students who are dyslexic is an inconsistent approach to spelling. They may spell a word one way on one day and another on the next. They will also typically make spelling mistakes with high frequency words and spelling errors will persist even as same age peers begin to develop their skills and make fewer errors in writing.

-

Flipping letter shapes, reversing letter combinations and writing in all caps. Many children with dyslexia have trouble with English letters that contain the same shapes, for example a lowercase b is a flipped version of a lowercase d. While it’s common for kids who are learning how to write to flip letters, when this behavior persists in second and third grade, dyslexia may be to blame. It’s also worth looking at the types of spelling errors students make. Reversing letters and struggling with vowels is more commonly associated with dyslexia. Teachers may also find dyslexic students prefer to write in all caps.

-

Messy writing and misuse of punctuation. Translating ideas into language and re-reading one’s own writing can be cognitively exhausting activities for a student with dyslexia. Very little mental capacity may be left over to deal with the more superficial elements of writing, such as producing neatly formed letters and observing punctuation conventions.

-

Trouble concentrating during reading and low comprehension. For dyslexic students it is often more difficult to get the meanings associated with words to stick long-enough to make sense of a piece of text. This is a result of a lack of automaticity in decoding and the cognitive weight of the reading task. Words may also be skipped over and anxiety about reading can further contribute to poor comprehension skills and an inability to stay focused.

-

Difficulty reading certain fonts, especially with flourishes. Just as it is easier for students with dyslexia to confuse same-shape letters they can also become visually distracted by flourishes and other embellishments added to words written in serif fonts. That’s why some teachers prefer to write in Arial or other sans-serif typefaces, to ensure every student finds printed text equally accessible. Learn more about dyslexia-friendly fonts.

-

Writing skills that don’t match speaking ability. Teachers will find that kids who are struggling with dyslexia generally employ a more limited vocabulary in writing exercises than they are capable of producing in speaking. They may also be quite bright, engaged and full of ideas, but unable to write them down. Their compositions can be hard to follow and there can be a general avoidance of free reading and homework that requires written responses.

Dyslexia strengths

In addition to literacy difficulties, there are also plenty of strengths associated with dyslexia including creative ability and out-of-the-box thinking. Dyslexics are often considered to be excellent problem solvers capable of bringing together ideas from very different domains and bridging information in a unique and exceptional way. Some people with dyslexia are also especially gifted with higher level reasoning and mathematics and it’s possible for children to be both gifted and dyslexic. Learn how to recognize the signs of a gifted child.

In order for teachers to encourage students to celebrate their strengths, it can help to provide role models in the form of famous individuals who have dyslexia. You may consider introducing both historic figures and current celebrities who have overcome the challenges posed by their dyslexia and harnessed their strengths to achieve success. Learn more in this article with motivational quotes concerning dyslexia.

After a diagnosis

There are plenty of strategies that can help a child with dyslexia improve their reading and spelling skills. Taking a multi-sensory approach to reading instruction is one, as is drilling phonics and providing plenty of repeat exposure to sight words.

Some students with dyslexia do well in regular classes given customized accommodations or the support of a private tutor, whereas others may benefit from a dyslexia specific track. It all depends on the severity of the dyslexia and the interruption it causes to learning.

Learn more about spelling strategies for dyslexia, classroom accommodations and helping dyslexic students thrive.

Additional Resources

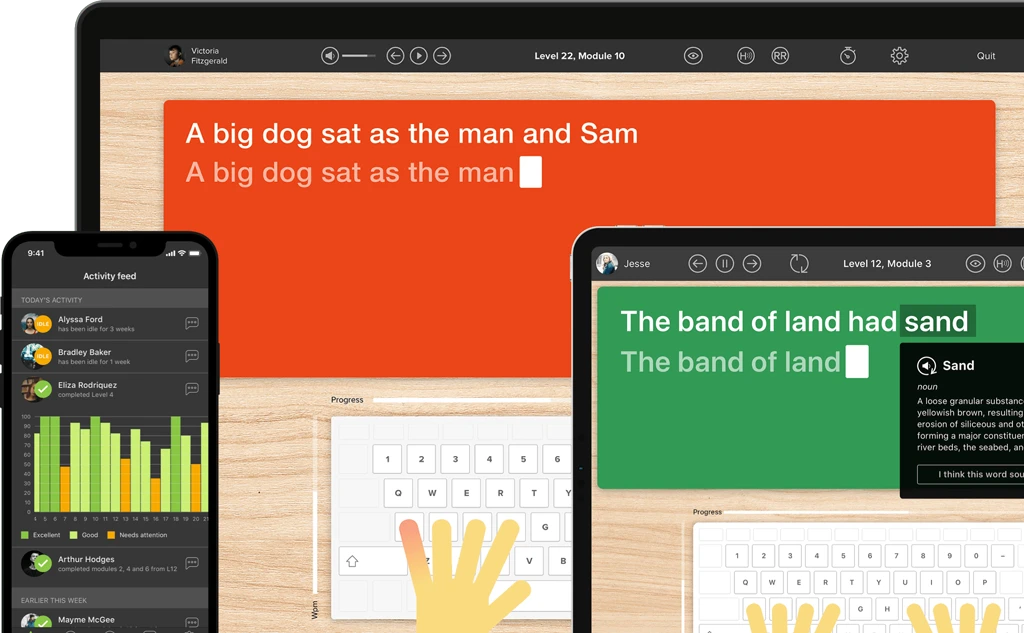

Touch-type Read and Spell has developed an award-winning and dyslexia-friendly course that teaches touch-typing, a skill that greatly assists the dyslexic student in and outside of the classroom. Instead of a traditional typing curriculum, with TTRS learners follow a phonics-based program that helps them learn the basics of English sound-letter mapping as they type out whole words.

Vocabulary appears on the screen and is played aloud as the student types the corresponding keys, combining sensory input to help language stick. Bite-sized modules allow users to repeat material as needed and learn at their own pace, building momentum and gaining in confidence as they go. Touch-typing is also one of the most recommended accommodations for students with dyslexia as it harnesses muscle memory in the fingers to help with spelling and can make it easier and faster for an individual with dyslexia to express him or herself in writing.

Learn more about touch-typing for dyslexics.

Help for older learners

Older students and adults with dyslexia may have developed coping strategies to help them get by at school. Nonetheless, they can still hide a secret shame or embarrassment when reading and writing are concerned. Some teenagers with untreated dyslexia leave school early and may choose a career path that doesn’t require reliance on literacy skills.

Nonetheless, adults with undiagnosed dyslexia can suffer from depression and a lack of confidence that causes them to miss out on career advancement or further education opportunities. Learn more about how to get help in this article on undiagnosed learning difficulties.

For learners who struggle with dyslexia

TTRS is a program designed to get children and adults with dyslexia touch-typing, with additional support for reading and spelling.

Chris Freeman

close

Can an Orton-Gillingham approach to literacy help your child?

Take a short quiz to find out!

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress