Recognizing an auditory processing disorder in children

An auditory processing disorder can cause difficulties with understanding in listening. It is not an indication of hearing loss or impairment, but rather a disruption to how the brain makes sense of sounds, including language. Kids with APDs are often labeled poor listeners at home and at school. This is because listening comprehension skills and memory for learning auditory information may both be impaired.

Auditory processing disorders, also called central auditory processing disorders, range in severity and no two individuals will experience the same set of symptoms.

A child may have trouble following conversations, particularly when there are multiple and overlapping voices.

They may have problems hearing the ends of words or distinguishing between words which sound similar.

Students with an auditory processing disorder can particularly struggle in the classroom, where background noise and echoes make it harder to focus on what the teacher is saying.

It may also be tricky for kids with an APD to follow directions provided aurally.

Parents and teachers might notice differences in speech production, particularly the pronunciation of certain sounds and placement of stress.

As phonological awareness is central to early reading, decoding skills can additionally be impacted.

How is an APD addressed?

There are a number of approaches that can help a child with an auditory processing disorder improve his or her confidence and skill.

Speech therapy assists with the perception of sounds, electronic devices can enhance and clarify audio signals, and self-monitoring strategies enable a learner to be pro-active about auditory distractors in his or her environment.

One of the most common classroom-based accommodations is supplementing auditory stimuli with visuals. For example, teachers may include a text-based version of a prompt.

Multi-sensory learning can also be a powerful technique for an APD.

Touch-type Read and Spell

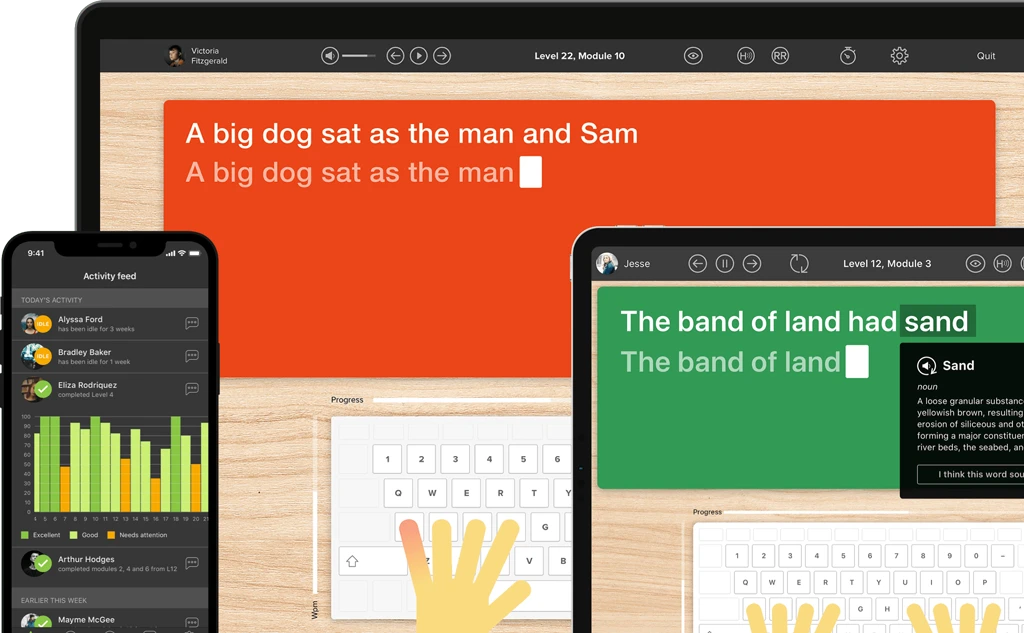

Touch-type Read and Spell is an Orton-Gillingham based typing program that has been used to help kids with an auditory processing disorder, ADHD and/or dyslexia learn keyboarding and familiarize themselves with English sounds. Words appear on screen, are played aloud and then typed, which combines visual, auditory and kinesthetic stimuli to reinforce language through a phonics-based curriculum.

Identifying children who struggle with auditory processing

A child who is overly quiet

Some students with APDs are overly quiet. Staying quiet is a way of preventing any embarrassment a child might feel as a result of giving an answer that shows he or she has not understood the question. Sometimes children avoid speaking because they don’t want to call attention to themselves and/or have problems with speech production. Over time, not engaging in speech with others can have serious social and emotional consequences. It can also make it harder for parents and teachers to identify the disorder, given there’s less evidence of comprehension problems.

A child who responds in unexpected ways

A child with an APD may respond in a way that shows he or she has only partially understood what has been said. It could also be that the response is completely unexpected given the child, the speaker, and the question. Some children may engage in attention seeking behavior at school in an attempt to distract teachers and classmates from listening problems – this is even more common when an APD and ADHD co-present.

A child who is hypersensitive to noise in their environment

Children with an auditory processing disorder may respond differently depending on the noise levels in their environment. You may find comprehension is improved in quiet, distraction-free spaces compared to environments with a lot of background noise, echoes or overlapping speakers. Loud environments can also provoke strong emotional responses in kids with an APD, including frustration, anger, and anxiety as a result of impaired comprehension.

Note noise sensitivity issues are often seen in dyspraxia and autism. However, dyspraxia and auditory processing disorder, and autism and auditory processing disorder can also co-present.

A child who has a hard time following instructions

Before a child can read, most task instructions are provided by parents and teachers aurally. This can be problematic because kids with an APD have a harder time understanding and remembering multi-step instructions, particularly if they are not repeated multiple times. The tragedy for children with a learning difficulty or disorder is they may be told they are not paying attention or deliberately disobeying the rules, when in reality they fail to follow instructions due to listening comprehension deficits. Learn more about building confidence in children with specific needs.

A child who has a hard time understanding people with accents

Children with an APD often have problems with non-standard speech sounds, including accents which are not familiar to them. That’s because regional accents in the child’s native tongue may vary in sounds, phoneme-length, stress, intonation and vocabulary. Individuals who speak with a foreign accent or speech impediment may be equally problematic for kids with an auditory processing disorder to understand.

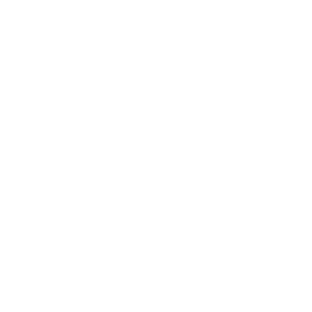

6 Ways to help students with an auditory processing disorder in the classroom

-

Provide visual cues.

You can help a learner enhance comprehension in listening by providing visual stimuli. For example, use gesture and hand signals or write questions and important points down on the board or on large flashcards. You might give students a handout with notes before you begin a lesson, which can help orient their listening. To support comprehension during a lesson, show slides with written text and images. You might also provide a written summary afterwards because seeing something written down can help with learning and retention.

-

Give them more time.

Because these kids often experience a response delay to questions, it can be useful to give them more time to both process a question and formulate an answer. You could work out a private hand signal, so you know when the child’s ready to respond to a question. Note, some children experience heightened levels of anxiety and prefer not to be called on at all. It’s useful to keep in mind that kids with an APD will get tired faster because listening is a cognitively taxing activity for them. Try to keep learning sessions short, give them plenty of breaks, and schedule activities at the right time of day. For example, it may be harder for a student to listen at the end of the school day when they are already tired.

-

Be aware of environmental distractors.

A child with an APD may wish to choose his or her own seat. It’s still useful to ensure there is no noisy air conditioner, heater or window close by. Keep in mind echoing voices from an open space (such as a gymnasium or school field house) or chatty students at a neighboring table can make it much harder for a student to hear what’s being said. Approach group work with care and if possible allow a student to work with just one partner in a quiet space. Overlapping voices can pose problems and when ADHD is present, social interactions may be strained. For after school studying or taking exams, a quiet desk space and noise canceling headphones are a good idea.

-

Pay attention to how you deliver spoken information.

Passive phrases or those with multiple clauses may be harder for students with an APD to follow because they require kids to hold more auditory information for longer amounts of time before it can be processed. Try to make your point up front and pause often. It might also be easier for a student to understand what you are saying if they can see your mouth while you are speaking. Avoid speaking too quickly or too slowly as speech rate can affect the delivery of sounds. Learners with an auditory processing disorder may struggle to hear emphasis in speech. Make sure to underscore key vocabulary and points in writing and to repeat yourself often, to facilitate comprehension and learning. Lastly, be aware that a student with an auditory processing disorder might not get all references, jokes, or figurative language if they are not written down.

-

Teach specific listening strategies.

Present pre-listening strategies. It is easier for the brain to process sounds and make sense of language if prior knowledge of a topic is activated. Have a learner look at titles and images and write out a mind map of language and ideas they expect to hear. Encourage them to make predictions and listen for keywords. Teach note-taking skills. Kids with an APD can make more sense of language when they see it written down, which also helps with memory. You might also have them record a lecture, so they can listen to it a second time. A speech and language therapist can provide training in specific listening strategies which help the brain deal with sounds more effectively, for example focusing on some sounds and tuning out others.

Overall, a child’s awareness of his or her own abilities is crucial. Teach kids to self-monitor and make appropriate adjustments at school– such as putting on noise canceling headphones, changing seats to see a speaker’s mouth or amplifying sounds with a device if needed. Let them know that there is no shame in informing others, including teachers, peers and family friends, they have an auditory processing disorder.

-

Reinforce language skills.

Depending on when a child’s auditory disorder was picked up, he or she may have been slower to develop reading and spelling skills. That’s because written language is a reflection of spoken language. Kids with an auditory processing disorder may have fuzzy phonological representations of words, which can make it harder to get the spelling right – and English spelling is already a challenge. If you don’t have a firm grasp of the difference between two sounds, it’s also more challenging to sound out the letters you see on the page.

That’s why a multi-sensory program of phonics can help these students immensely. It entails a learner seeing a word written down and hearing a clear audio recording that they can repeat if necessary. It’s even better if the program introduces language in sequence, to reinforce the difference between minimal pairs and teach vocabulary words that are useful for completing school work.

More about auditory processing disorders

How common are they?

It has been reported that 3-5% of children have problems processing auditory information. Problems may become more evident when they start attending school.

What causes them?

There is no one cause of an auditory processing disorder.

The fact that it can run in families suggests there may be a genetic component, but other research has pointed to a relationship between conditions which damage the ear or brain and a tendency to develop an APD.

How do they test for them?

As auditory processing is different from hearing ability, tests will typically check first to ensure there is no hearing impairment which is causing problems with how the ears receive and process sounds.

A child may then perform comprehension and auditory decision tasks in which properties of the speech signal and environmental noise are varied.

Some tests will focus on ability to recognize sound patterns and hear changes in sound, whereas others may even measure brain activity in listening.

How is ADHD different from an APD

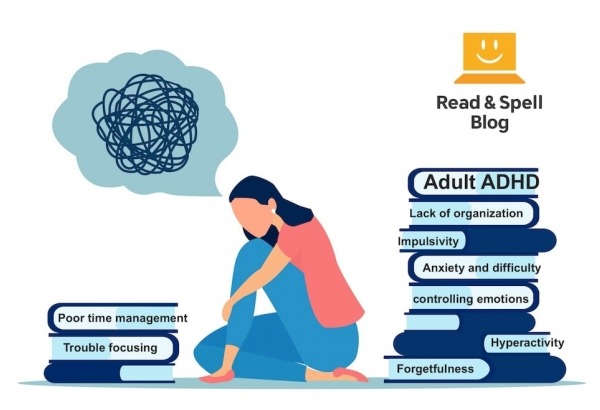

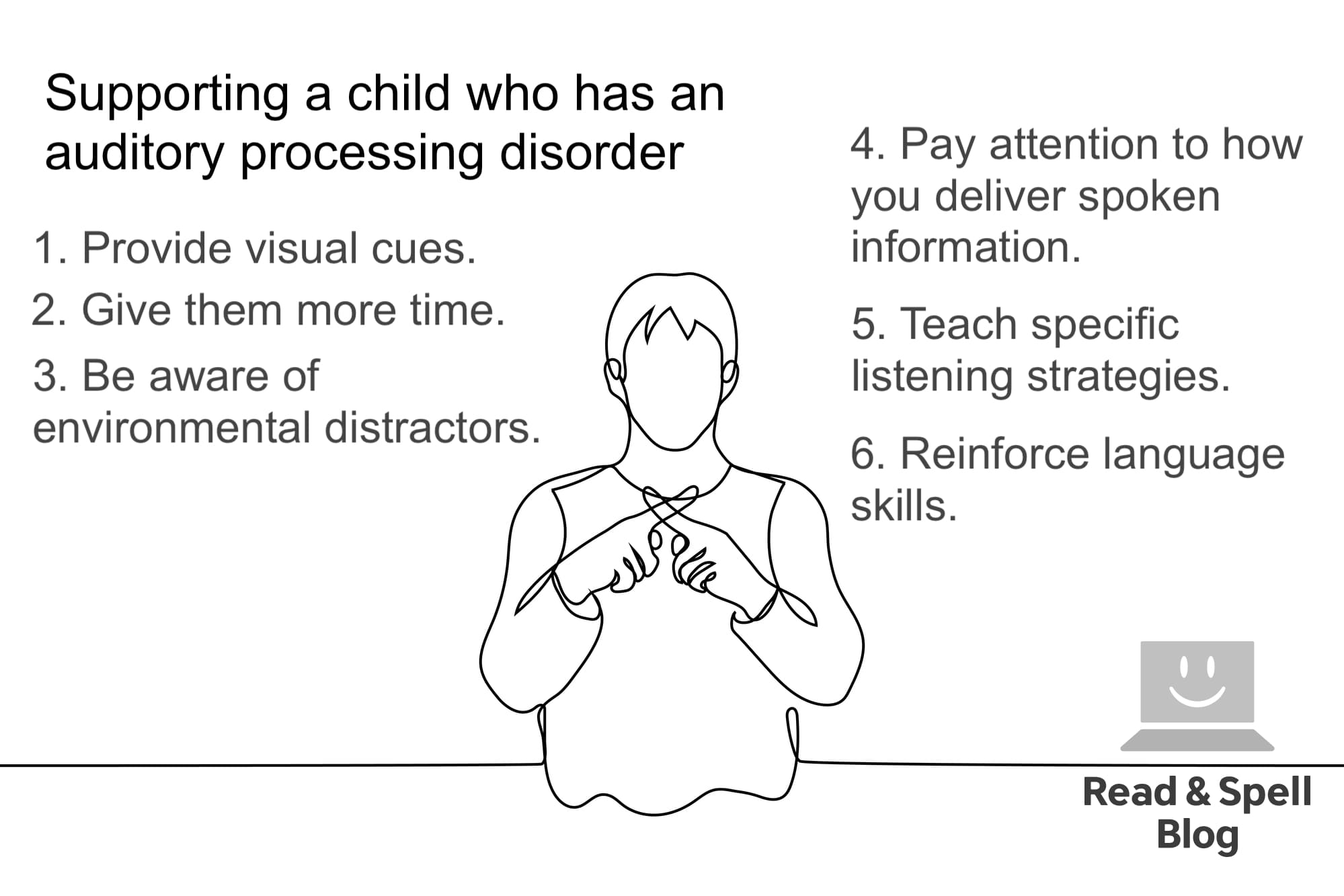

ADHD is an umbrella term that describes attention difficulties both with and without hyperactivity. ADHD and an APD are not the same disorder, but they can co-present.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports 11% of school age children between 4 and 17 have some form of ADHD, and some websites, including ADDitude, suggest up to 50% of individuals diagnosed with ADHD also have an APD.

As public awareness is more common for ADHD than APDs, it is possible some cases of auditory processing disorder are misdiagnosed as attention disorders.

For example, when a child with an APD has a hard time focusing, gets frustrated during listening activities, or doesn’t follow directions, it may not be they are tuning the teacher out but rather that they can’t process the sounds they are hearing.

More on TTRS

An APD can cause academic delays where reading and writing are concerned and can generally undermine a student’s ability to be successful at school.

Building phonological awareness is an important first step for the child with an auditory processing disorder who also has literacy skills deficits. Making it easier to take notes and get thoughts down on paper should be another key focus.

Touch-type Read and Spell is a multi-sensory typing program that teaches kids with special needs and attention difficulties how to master keyboarding.

It presents lessons in short modules that are manageable for learners with ADHD and dyslexia, and includes high quality audio recordings so words are shown on screen and played aloud, to reinforce the associations between sounds and letters.

The course teaches typing via a whole-word approach grounded in phonics, but it also aims to build confidence and self-esteem in learners through a gentle and accuracy driven approach.

Kids with an APD often have problems learning rote facts. TTRS has lessons that cover math and science so arithmetic facts and subject vocabulary are read, typed and listened to, which enhances learning and retention.

For teachers

TTRS is a program designed to support educators in teaching students touch-typing, with additional emphasis on reading and spelling.

Chris Freeman

close

Can an Orton-Gillingham approach to literacy help your child?

Take a short quiz to find out!

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress